We are surrounded by mortality -here in the country we considered safely above epidemics, and in the world at large. This kind of widespread death shocks us from the comfort of our everyday denial of death. The human being’s constant background denial of their own mortality allows them to go on day to day, to plan for the future, but also it expedites our passion for worrying about that which is truly pedestrian, not worthy of our precious time here on earth.

The Talmud in tractate Berachot states that if one is struggling with the evil inclination they should try four things, first, utilize one’s good inclination to overpower the evil one, if that does not work then study torah, if that does not work say the shema and if that does not work think of the day of death. Literally, “yizkor lo yom hamita, remember to him the day of death.”

Rabbi Gedalia Silverstone in his 1901 commentary on tractate Berachot, Pirchey Aviv, asks on this piece of Talmud, why it states, “yizkor lo yom hamita, remember to him the day of death.” It could have just said, “remember the day of death.”

He answers that remembering the day of death is not enough. It must be remembered to us. Many people, Rabbi Silverstone says, see death with their own eyes, but still it does not change the way they act because they only see death in the other, they do not make the jump to remind themselves that the bell will toll for them too.

The unconscious denial of death that we all engage in can lead to dangerous and unethical outcomes. Ernest Becker in his classic book, The Denial of Death, wrote, “Humanity literally drives itself into a blind obliviousness with social games, psychological tricks, personal preoccupations so far removed from the reality of the human situation that they are forms of madness -agreeded madness, shared madness, disguised and dignified madness, but madness all the same.”

Becker goes on to highlight some of the ways that this need to deny death plays out in our world. For instance, he says that prejudice and hierarchical groupings emerge from our desire to place ourselves above others, the others who are not as good, or not as smart, not as special as us, thus fooling ourselves into thinking that only they will die and not we -we are special, we will be spared.

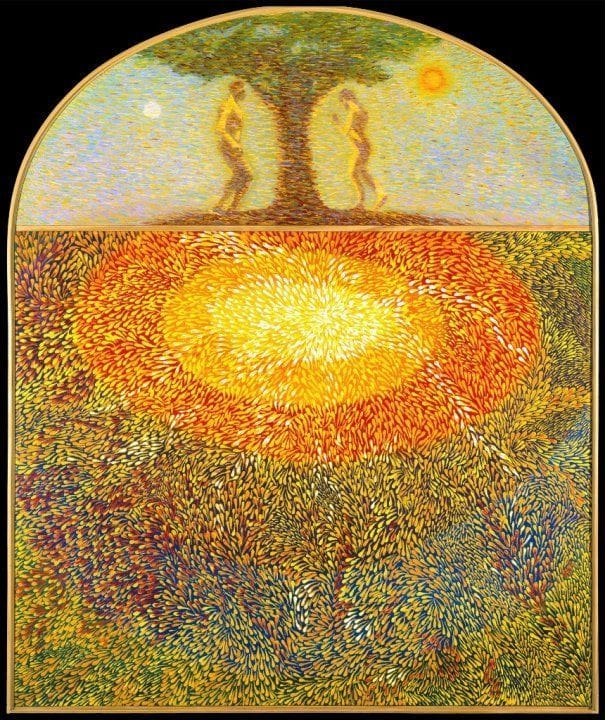

We know well as a society that many other things at their base are there to distract us from the fact of our mortality, such as entertainment, the pursuit of wealth, honor or pleasure as an end in itself, culture, and so much else. But the awareness of death, though scary, can be very positive. As Irvin Yalom put it, “Death and life are interdependent: though the physicality of death destroys us, the idea of death saves us. Recognition of death contributes a sense of poignancy to life, provides a radical shift of life perspective, and can transport one from a mode of living characterised by diversions, tranquillisation, and petty anxieties to a more authentic mode. (Existential Psychotherapy)”

This is an anxious time of fear, mourning and introspection. How can we use our experience of the Corona epidemic to not just let it produce within us anxiety whose outlet, in service of avoidance, is merely prosaic and a waste of time, but instead to refocus us personally and our world generally on equity, compassion, meaning, morality, ultimate purpose, and the subtle but deep things which reside within inside us but we are afraid to encounter?